May opened with a grand display of ritual; people in ‘funny clothes’ held

captive to tradition as a crown was placed on the head of a man in England.

Millions watched, mildly embarrassed that they were actually enjoying a show

that seemed to have no relevance to real life. May closed for some hundreds of

us as we watched a graduation ceremony at Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare

where people also wore funny clothes as they rejoiced in the spectacle of a cap

lightly touching the head of each of the graduating students.

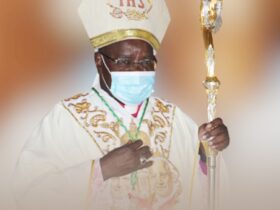

Both events were heavy in ritual. I became aware of this as the AJU procession

entered the great hall at a slow pace, two by two, led by a student carrying a

large standard and another carrying a shield. The lengthy programme, longer

than the coronation (!), was marked at every step by protocol and someone

saying, ‘By the powers invested in me …’

Why do we submit to ritual? What is the point of it? The British ‘mother of all

parliaments’ is held together by ritual. When speaking you do not address your

adversary directly but through ‘Madam, or Mr, Speaker’, the chair person. This

‘de-personalises’ the confrontation and raises it to a higher level. You are

seeking clarity of thought not victory over an opponent.

Years ago I studied the ceremony of Kurova Guva, the final event performed

when someone dies. I forget many of the details but I always remember the

narrator saying, ‘if you fail to do a particular step in the process, improvise.’ As

I understood it, this means you can make a mistake or leave out something but it

doesn’t matter so long as the basic function of the ritual is adhered to. In the

recent commentaries on the coronation in London, reference was made to an

earlier such occasion when an archbishop couldn’t find the right page or some

symbolic implement was forgotten. It did not matter. The ceremony ploughed

on.

Ritual, religious or secular, carries us forward. It places us in something larger

than us. Left to ourselves, without any socially visible mark of our progress –

birthday, graduation, marriage, ordination, inauguration, jubilee, funeral – we

can wither. Ritual provides a frame of reference which we can note and

celebrate. It reminds us of the bigger picture, beyond our little selves. It gives us

a life support system to carry us through difficult moments. If a person, for

instance, is committed by a solemn public promise when they wed, it helps

them, if they are going through a rough passage in the marriage, to remember,

‘I’m committed to this. Why turn aside now just because things are a bit

tricky?’ The same is true of priests. We are all held and supported by the public

commitments we make. ‘Ritual’ may sometimes have a bad name, but it can

serve us well.

By Fr David Harold-Barry SJ

Leave a Reply